Gates of Justice — Sasha Okun

- Shlomit Oren

- Dec 14, 2025

- 6 min read

Already upon entering the Dina Recanati Foundation space, it becomes clear that Gates of Justice is an extraordinary artistic event.

Descending into the space and standing at its centre, the work surrounds the viewer from all sides.

The heart overflows, flooded with emotion.

Gradually, those emotions begin to crystallize—into pain, attraction, humour, and repulsion.

All of these coexist within the work, and much more.

Gates of Justice may well be the final work of artist Sasha Okun, and it stands as a monumental culmination of his oeuvre. Okun worked on it between 2023 and 2024 as a requiem for his wife Vera, whom he cared for through illness and dementia. Yet it can also be read, to a great extent, as a requiem for himself—created while he was simultaneously battling pancreatic cancer, which ultimately claimed his life.

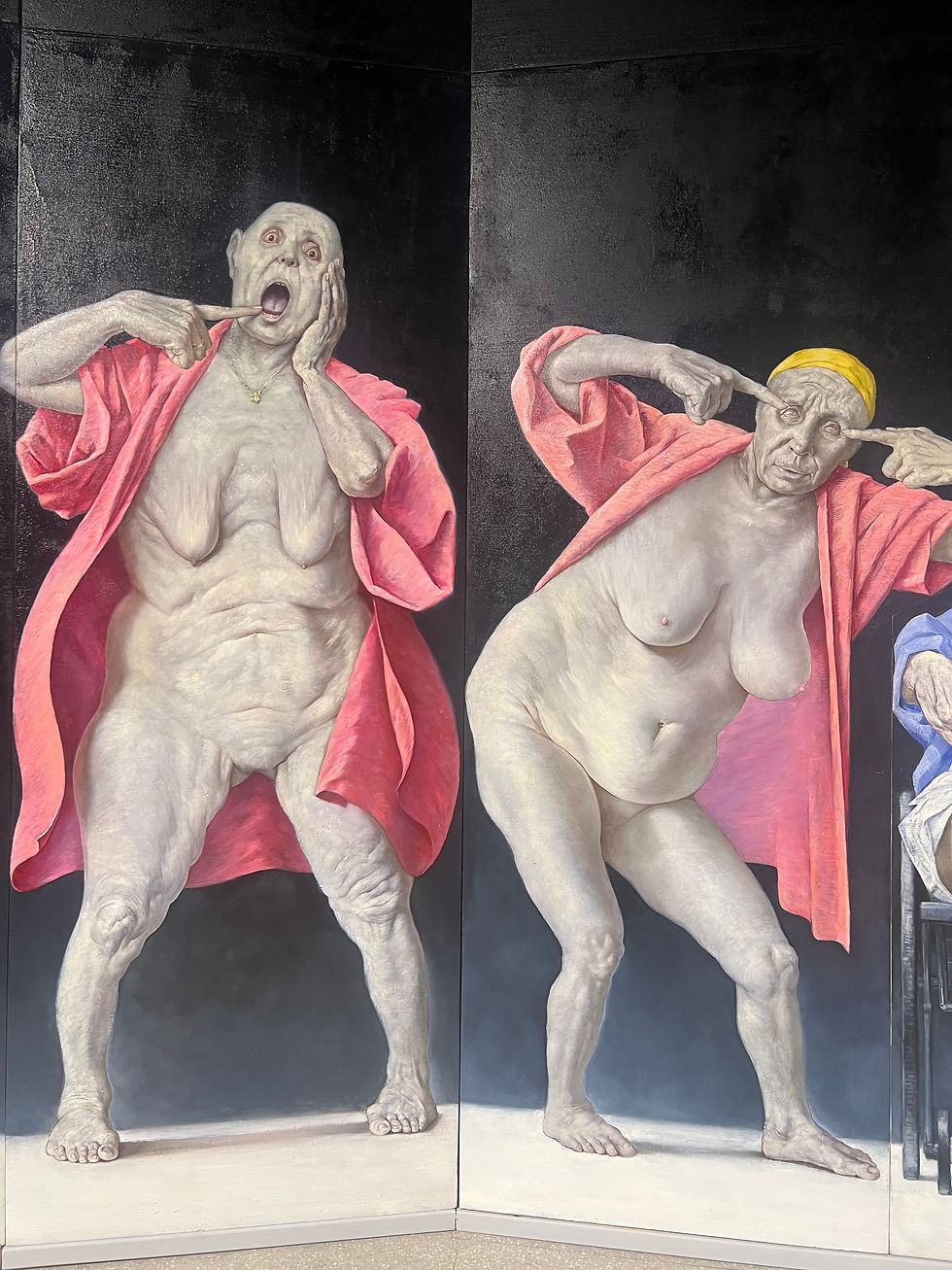

The work stretches 14 meters in length and rises 4 meters high, composed of dozens of wooden panels painted in oil. Thirteen figures appear in the composition, echoing The Last Supper, though here the scene feels closer to the Day of Judgment. Okun’s figures are based on a mixture of friends and loved ones, arranged under the influence of situations he encountered in hospitals—moments in which people lose self-awareness and regress behaviourally to childhood. With remarkable skill, Okun confronts us with the seemingly inconceivable connection between old age and infancy: bodies marked by time and decay, while facial expressions and gestures are liberated from social conventions.

Okun was something of a playwright, and his characters are shaped through a grotesque infused with compassion, making us laugh and cry simultaneously, as if pulled from one of Hanoch Levin’s plays. Known for his deep familiarity with culture in all its forms, Okun integrates numerous references to artists and works from art history. His painted figures resemble monumental marble sculptures, in the tradition of Michelangelo and his successors. These sculptures were intended to be viewed from below, resulting in deliberate distortions—shortened legs and elongated torsos. The bodies’ coloration recalls marble as well, yet they are far from smooth or idealized like those of Michelangelo, Bernini, or Canova. Instead, folds of skin and wrinkles resemble the Judean Desert landscape, which Okun loved to hike—its hills and ravines. Okun often spoke in praise of the “unbeautiful” body, quoting Rodin’s assertion that “beauty in art is character.” In his later years, he devoted his painting to depicting the aging human body without embellishment: protruding bellies, sagging breasts, stretched and wrinkled skin—yet persistently insisting on revealing its beauty.

Art history enthusiasts will recognize the use of Vermeer’s blue, which Okun mixed specifically for the robes of some figures, while others are clothed in colours reminiscent of Raphael’s paintings. Clothing adds vitality and colour, yet does not serve as concealment. Its style is indistinct, tied to no specific fashion or era, rendering the figures timeless. The choice of a black background serves the same purpose: this is a scene detached from any familiar time or place.

One elderly figure seated in a wheelchair extends his leg forward, revealing a dirty foot—a clear reference to Andrea Mantegna, the first to depict the human body in such dramatic foreshortening, most famously in his shocking portrayal of Christ with dirty feet.

Many of the figures use their index fingers to point toward their source of illness—eyes, belly, breast, and more. The figure just right of centre points to his head in a gesture reminiscent of God’s hand giving life to Adam in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling. All the hands in the painting are oversized, emphasizing their importance.

At the centre of the composition two figures stand out, dressed in contemporary clothing and clearly anchored in the here and now. The central anchor is the doctor, wearing green surgical scrubs and red sneakers. His hands are open, turned toward us in helplessness. The pose recalls Christ in Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, and other depictions in which Christ displays his stigmata. Here, however, the opposite is true: the doctor presents hands untouched by God. His eyes are closed; he does not meet our gaze. He has no ears—he can no longer hear the pleas of the patients. In an earlier version of the work, the doctor’s hands were raised and his eyes open. In the final version, though, there is nothing more he can do; he is powerless, surrendered by illness and death. The doctor is the only specific figure in the work—it is Okun’s own personal physician.

Beside him stands a nurse. She turns to him, holding her hands together in prayer. She is the only figure who still carries hope for redemption. That hope lies in her womb—she is pregnant, destined to bring forth the next generation, and thus stands in contrast to all the others.

Okun was an avid lover of classical music and used to listen to it while painting. He also believed his works should possess musical rhythm—a cadence guiding the viewer’s gaze. In the full composition, this becomes evident: at both ends stand men cloaked in light blue robes, holding IV poles, marking the passage through the Gates of Justice. The figures between them and the doctor and nurse vary in height—some seated, others bent—avoiding a uniform, monotonous “chorus line.”

In interviews throughout the years, Okun stated that he was not seeking to present something new, as many contemporary artists do, but rather the truth. Truth in painting is not necessarily faithful depiction of reality. He likened painting to translation: literal translation often misses the essence and fails to convey the author’s intent. For example, the English saying “Don’t judge a book by its cover” becomes awkward when translated word-for-word into Hebrew, and is instead rendered as “Don’t look at the jug, but at what’s inside it”. Similarly, the painter takes artistic freedom to convey the truth he seeks through painting. For Okun, the most important truths—the most serious matters—must not be taken too seriously. Hence the injection of humour into his works. He defined his genre as tragi-comedy.

Even after hours of contemplation, Gates of Justice cannot be fully deciphered. Mystery was always present in Okun’s work—something elusive, impossible to resolve, yet essential. It is precisely this mystery that activates the work anew with every encounter.

Sasha Okun immigrated to Israel from the Soviet Union in the late 1970s. His style did not align with the prevailing artistic trends in Israel, and he therefore worked on the margins, an outsider for most of his life—despite having raised generations of students and admirers at Bezalel Art Academy (though not within the art department). In the final months of his life, perhaps not coincidentally, Okun experienced a revival, with exhibitions at the Petah Tikva Museum and the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Yet his greatest masterpiece was shown abroad: in September 2024, Gates of Justice opened at the Albertina Museum in Vienna, thanks to Okun’s major patron, Michael Marks. Seeing the publications about that exhibition, I regretted that such a profound talent, cultivated in Israel, was not being shown here. I was thrilled to find that Hagai Segev, curator at the Dina Recanati Foundation and Okun’s close collaborator for two decades, worked tirelessly to bring this monumental piece to Israel, even if only for a few months. Due to spatial constraints, the work is installed in a semicircular arrangement, however, in my view this placement is powerful and generates an intense emotional experience. It is not every day that one stands face to face with a masterpiece. Gates of Justice is undoubtedly one.

Sasha Okun was present at the exhibition opening. Only ten days later, he passed away.

Sadly, I never had the opportunity to meet Sasha Okun personally, and the more interviews I read and videos I watch, the more I regret it. He possessed a deep humane quality, rich in intellect and charm. I was astonished to learn that he delivered a masterful guest lecture on drawing at Bezalel only about 24 hours before his death—almost unimaginable.

Okun loved life and celebrated it. This is evident in his work, including Gates of Justice. It is also evident in the final message he asked his daughter to send from his phone upon his death: “I have set out on my final journey—in other words, I have died. Come to the funeral and the shiva. You are all more than invited!”

Comments